EDITOR'S PICK

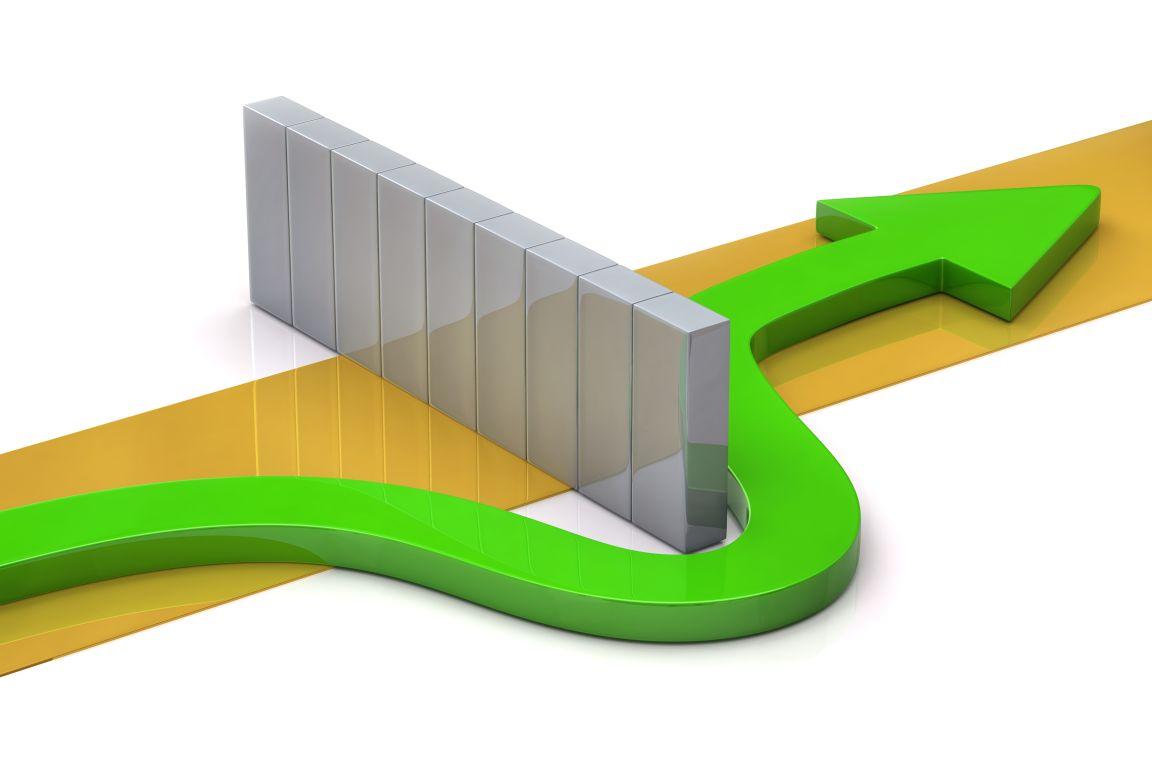

Stop trying to make firewalls happen: What IT can learn from Tesla about disrupting the status quo

Jan 24, 2022

Is it better to continually optimize the status quo? Or reject it and create something better? Those are questions professionals in the tech sector should constantly be asking themselves.

“The most common error of a smart engineer is to optimize a thing that shouldn’t exist.”

– Elon Musk

Is it better to continually optimize the status quo? Or reject it and create something better?

Those are questions professionals in the tech sector should constantly be asking themselves. The first option seems safer and easier and attracts many decision-makers by default. But many of the most profound and successful innovations in the history of technology have emerged by pursuing the second premise, however crazy it may seem. Apple founder Steve Jobs wasn’t wrong when he pointed out that, "The ones who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do."

Serial innovator and Tesla CEO Elon Musk was willing to reject the status quo and build something new. Traditional manufacturers of gas-powered cars seek to optimize the combustion engine, something they’ve been doing with varying success for more than a century. With Tesla, Musk took a different approach. Tesla wouldn’t continue to tweak the combustion engine for small performance gains. In fact, Tesla cars wouldn’t even have a combustion engine. Something better – an electric motor – would replace it entirely.

Tesla didn’t invent the electric motor. But shifting from gas to electric power was transformational. Such a rejection of the status quo can – and should – be applied to tech industry product development. But change (especially radical change) is hard for many to embrace, and most tech companies choose the easier, safer route: prioritizing small enhancements to existing architectures, or adding superfluous features to augment old products.

Replacing the status quo with something fundamentally superior – usually something simpler – is a better strategy in the long term, especially when applied to cybersecurity. Reimagined, simpler solutions can deliver extraordinary advantages. They can reduce operational costs, eliminate user performance issues, and dramatically increase security posture.

Minimize moving parts to enhance the Zero Trust value proposition

Consider this: Combustion engines have around 2,000 moving parts. Electric motors have twenty. That’s two orders of magnitude fewer parts for Tesla to have to install and configure; far fewer parts to wear down gradually over time or require replacement. The electric motor paradigm is elegant in its simplicity and the benefits it delivers.

There is a similar contrast between the complexity of legacy security infrastructure and the elegant simplicity of the Zero Trust security model.

Traditional, outdated “castle-and-moat” security architectures were designed to protect work performed within the castle walls of a conventional network perimeter. Legacy solutions like firewalls and intrusion prevention systems aimed to keep out the bad guys.

Only now, work is performed outside that network boundary, in the cloud, or on the internet. “Simplicity” and “efficiency” no longer apply to traditional security infrastructure technologies, which have become increasingly complex, unwieldy, costly, and awkward for security professionals to manage, all in the (futile) effort to preserve an outdated security model for a new way of work. (How do you secure a perimeter around the open internet?) The result is weakened security, poor performance, and exploding costs for maintenance and overhead.

Meet the new boss, different than the old boss

IT security teams’ efforts to sustain the castle-and-moat security model in the face of growing threats is at best counterproductive and at worst dangerously risky to the enterprise. The Zero Trust security architecture model rejects that outdated (and unsecure) status quo entirely.

With Zero Trust, security policy is applied based not on assumed trust, but on context established through least-privileged access. Zero Trust moves focus from connecting entities to a “secured” network to securely connecting entities directly – user to application, workload to workload, or even IoT/OT device to resource. Zero Trust does not assume communication is secure simply because it originates inside the network perimeter. Instead, Zero Trust requires authentication and validation in every case, no matter where the entities may be.

Such a fundamentally different approach delivers simpler security because it no longer matters where users are, where applications are, where data is, or where physical hosts are. (Contrast that with legacy infrastructure appliance stacks that must be replicated, operated, and maintained in each branch office.) With Zero Trust, the same core security model always applies, and always delivers the same key benefits. That holds whether an internet user connects to an on-premises application, an application connects to a public cloud service, or anything else connects to, well, anything else.

Compared to castle-and-moat, Zero Trust is elegantly simple. Zero Trust is easier to manage, faster-performing, less expensive to maintain, and far more flexible than legacy security infrastructure. More importantly, it provides better security. With no attack surfaces, breaches are prevented, data and applications are protected, and IT infrastructure – what remains of it – delivers more business value with less risk than ever before.

IT decision-makers need to reevaluate the status quo. Does a traditional firewall still deliver enough value to justify implementing and managing it? Should inbound and outbound security stacks at each office location continue to be supported? Is it worth it to continue to manage different security protocols (VPNs) for remote users than for on-premises users? The potential of a Zero Trust future answers those questions. (No, no, and no.) The status quo must go.

So, is castle-and-moat worth sustaining with incremental optimizations? Or have we simply reached the point where it shouldn’t exist at all?

Recommended